THEMIS Vistas

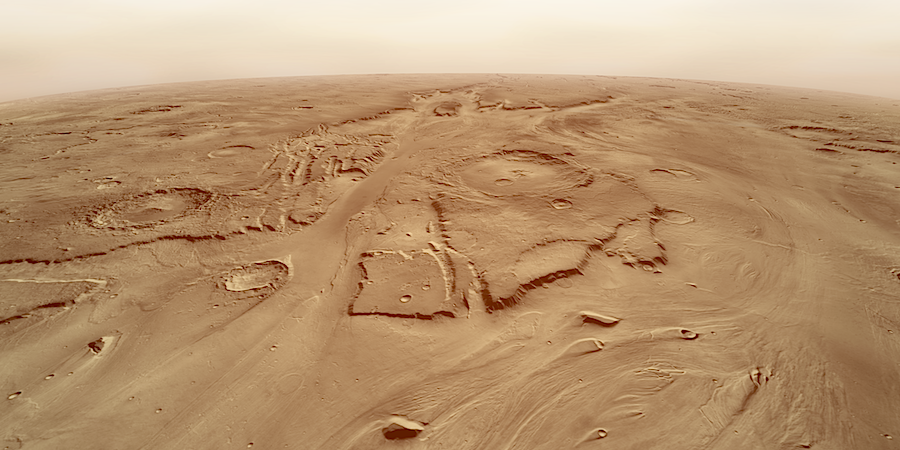

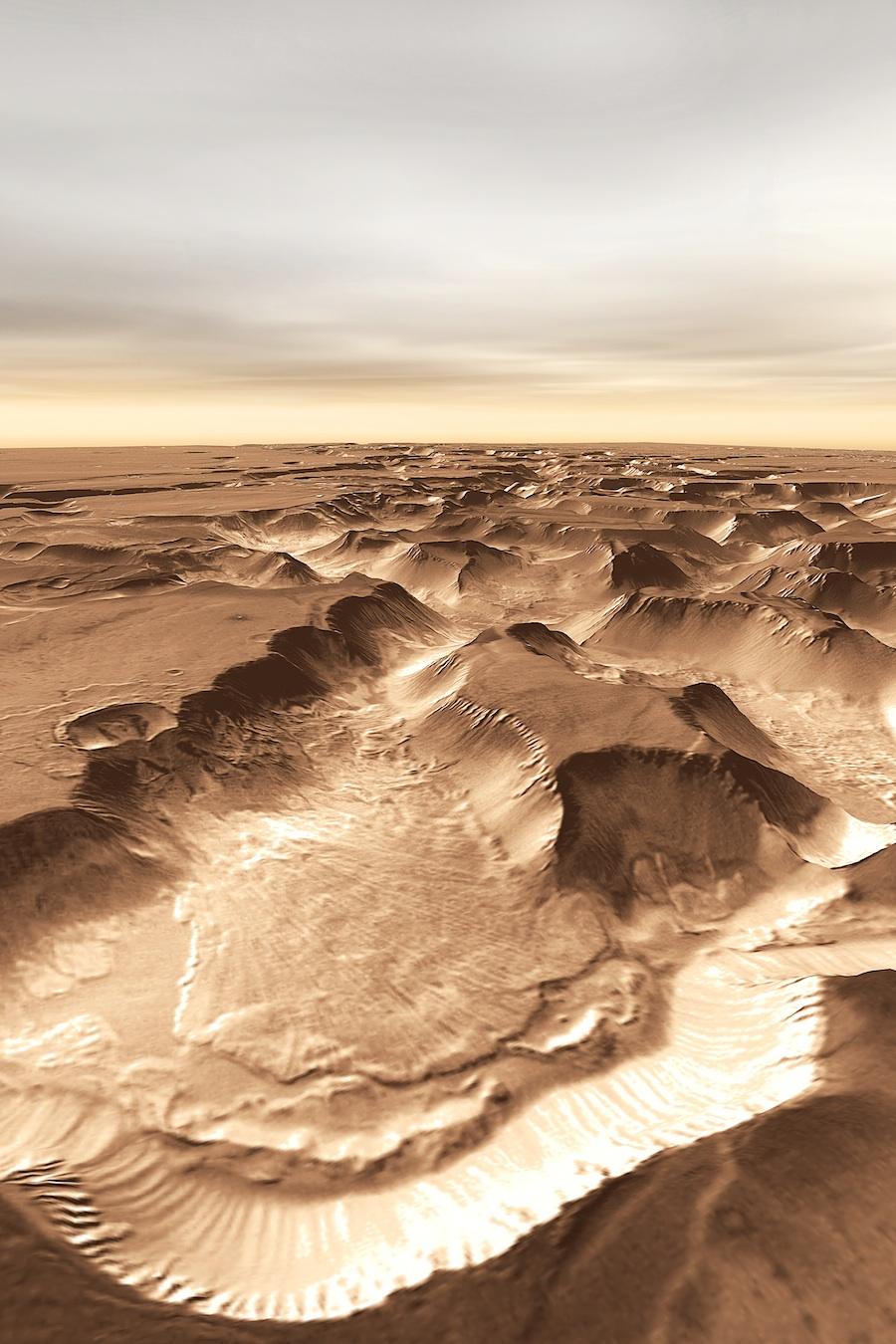

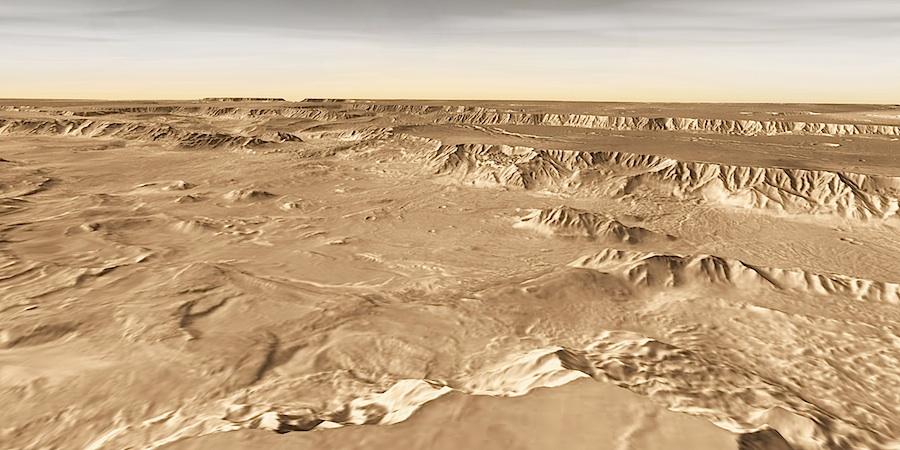

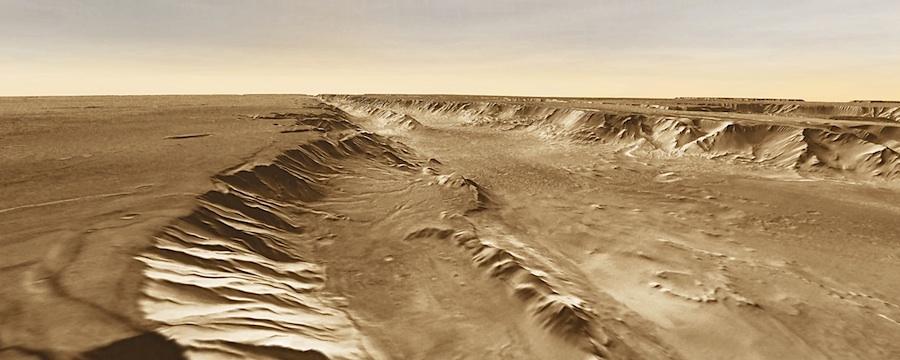

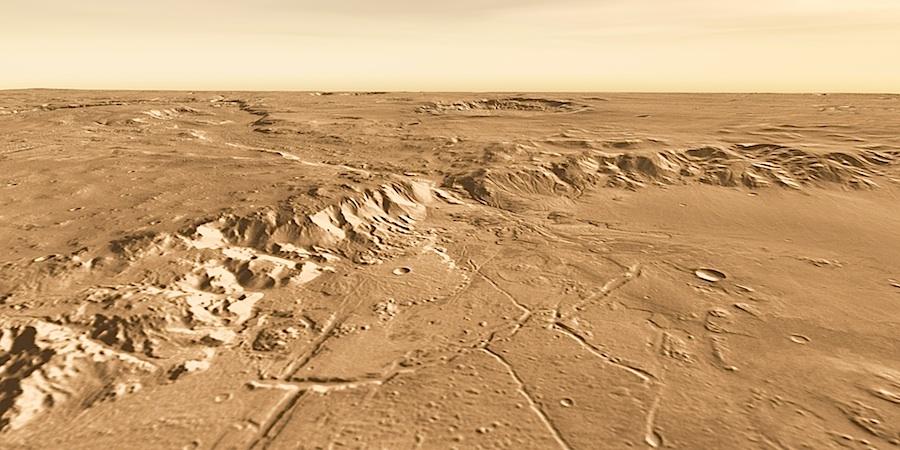

MEGAFLOOD CHANNEL. Kasei Valles is the largest and longest flood spillway on Mars. It runs more than 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) north across Lunae Planum before turning east and emptying into the Chryse Planitiia basin. We are looking west (upstream) from an altitude of about 150 kilometers (90 miles). In the distance, it appears that there are two separate channels, yet both are part of Kasei. The large crater on the mesa in the center is Sharonov, 100 km (62 mi) in diameter. This view has a vertical exaggeration of 2x, and a 10 MB version of the image is available. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore Kasei Valles further, see The Cataracts of Kasei. |

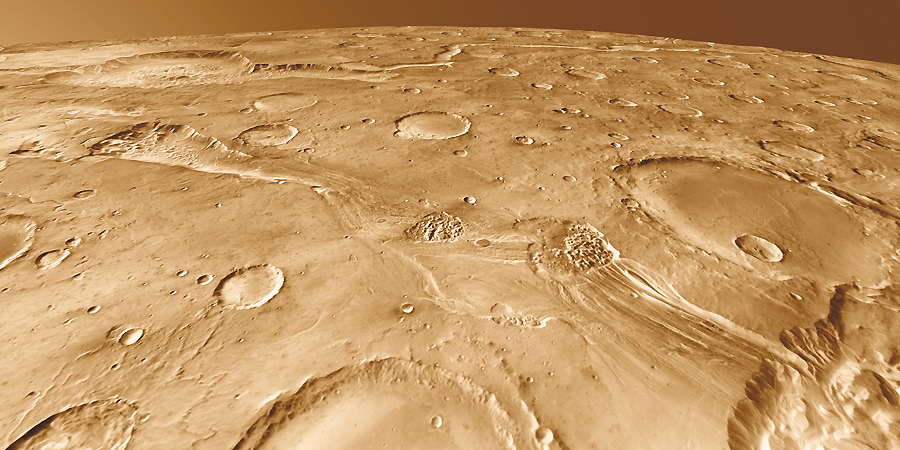

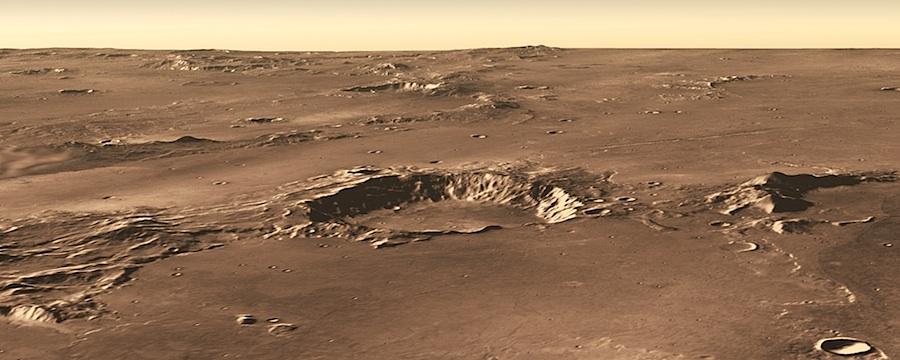

SHORT, FAST RUN. Around 200 kilometers long, Ravi Vallis was born in a flood of water from Aromatum Chaos (left). The racing waters sliced a pathway across Xanthe Terra, spawned at least two small chaos regions in the channel (center), and then hurtled over the plateau edge to disappear into another chaos region (right foreground). In the distance at left lies Orson Welles Crater and the meandering path of Shalbatana Vallis, a much longer outflow channel perhaps related hydrologically to Ravi. This view looks northwest from an altitude of about 120 kilometers (75 miles); vertical exaggeration 1.5x. (A 6.1 MB version of the image is available.) Image credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore the Ravi/Aromatum system further, see A Flash In the Valley. |

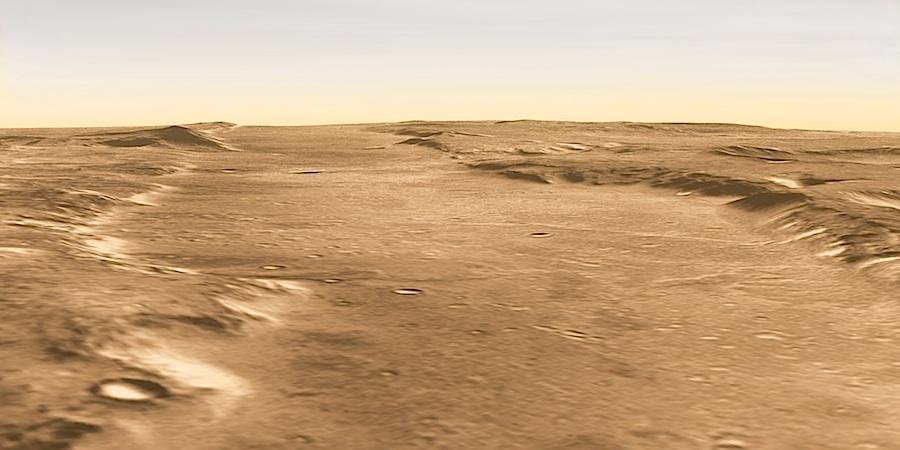

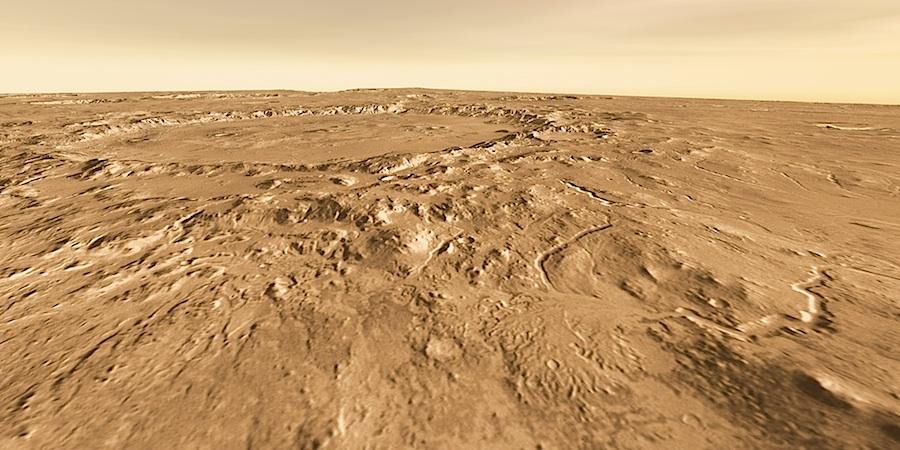

KEEPING A LOW PROFILE. Tyrrhena Mons is one of a handful of low-elevation, easily eroded volcanos that lie next to the Hellas impact basin. Among the oldest known volcanos on Mars, Tyrrhena shows marked differences from large and lofty volcanos such as Olympus Mons. It's not even 2 km high compared to Olympus' more than 20 km, and instead of being made from flows of hard, basaltic lava, Tyrrhena was built from numerous explosive eruptions that spewed mostly cinders and ash. This view looks north from an altitude of about 20 kilometers (12 miles); no vertical exaggeration. (A 1.2 MB version of the image is available.) Image credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore Tyrrhena Patera further, check out Not the Typical Mars Volcano. |

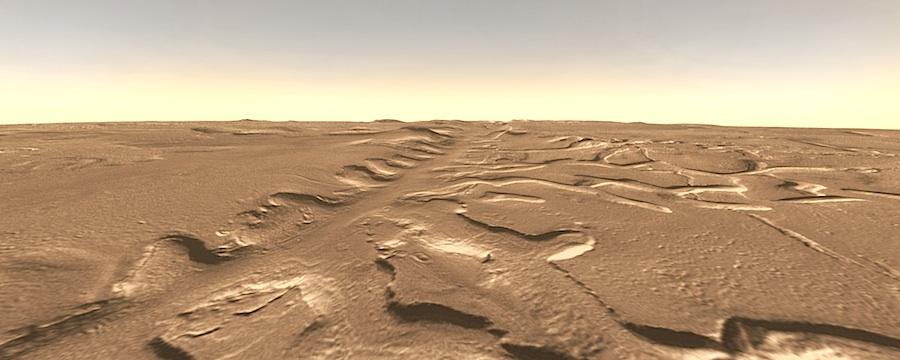

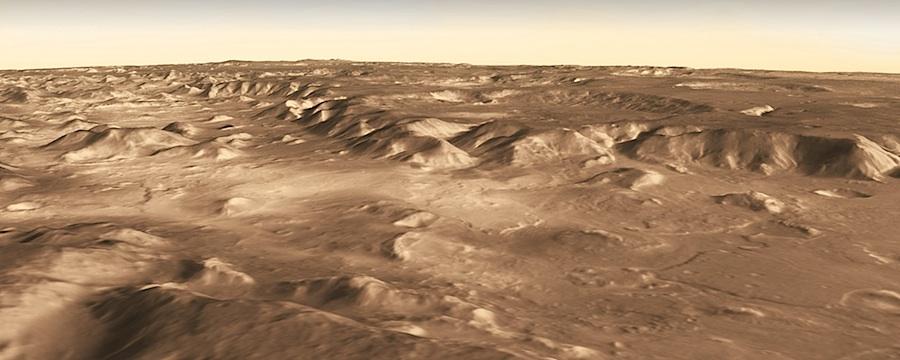

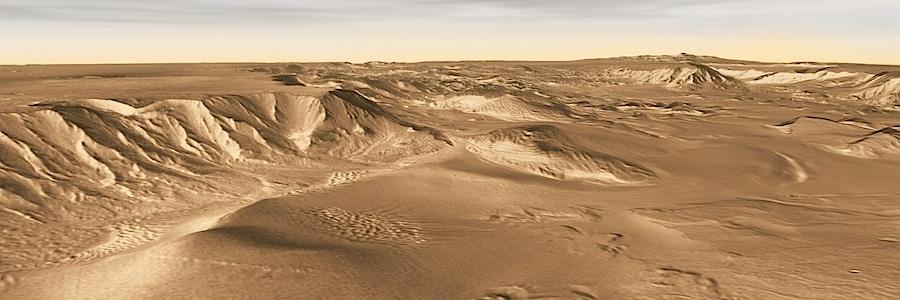

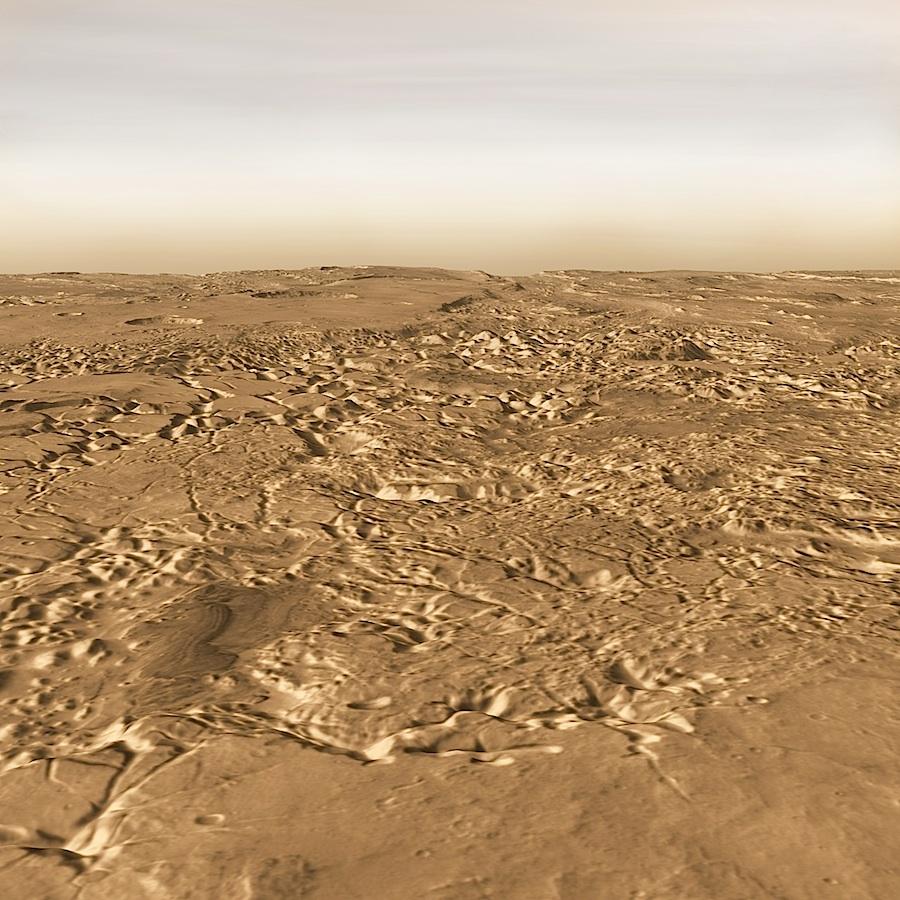

SHARP WINDS. Memnonia Sulci, seen here, is a small part of a giant geologic unit named the Medusae Fossae formation. Believed by scientists to be comparatively young, the formation has been extensively eroded by winds that have carved the soft materials into long ridges called yardangs. The formation's nature is unknown, but scientists think it may be mostly volcanic ash. This view looks northwest from an altitude of about 20 kilometers (12 miles); no vertical exaggeration. (A 4.6 MB version of the image is available.) Image credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore Memnonia Sulci further, see Where the Wind Has an Edge. |

PLANETARY ARCHIVE. A thick stack of sedimentary debris stands in Gale Crater, a possible target for exploration by NASA's Mars Science Laboratory. This view looks southwest, toward the crater's central peak in the left background. (A 4.3 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this feature in greater depth, check out Gale Crater's History Book. |

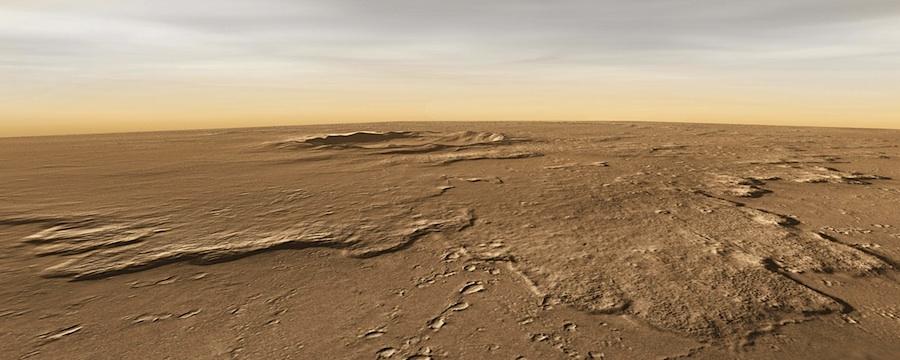

RUNNING STRAIGHT toward the horizon, Galaxias Fossae carves a line across Mars' Utopia plains. The channel formed in ground laden with ice and water when a ribbon of molten rock rose within a geologic fault. The heat triggered the escape of water, undermining the surface and creating a network of shallow channels. This view (which has no vertical exaggeration) looks west. (A 360 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk.To explore this area further, see Galaxias Fossae: The Fire Below. |

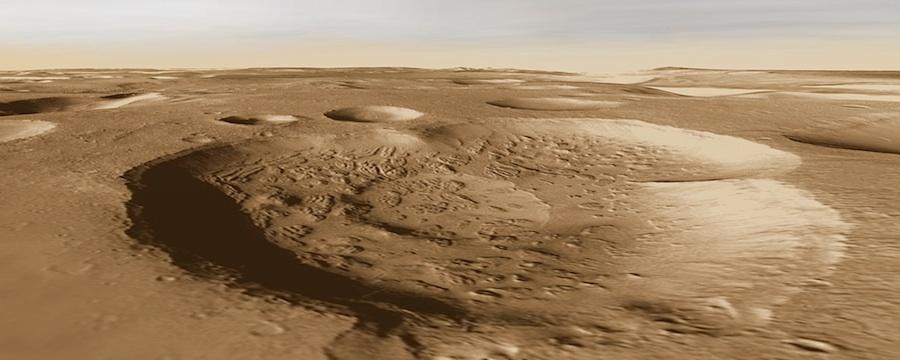

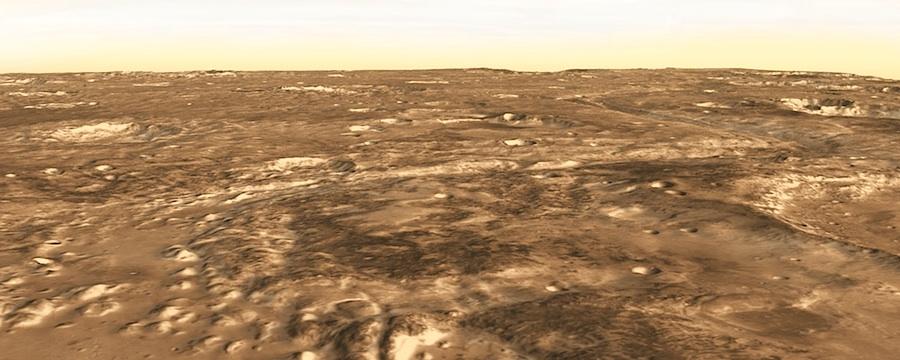

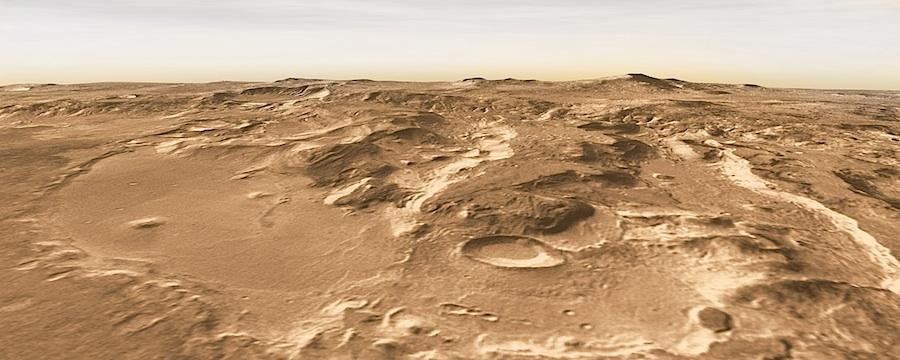

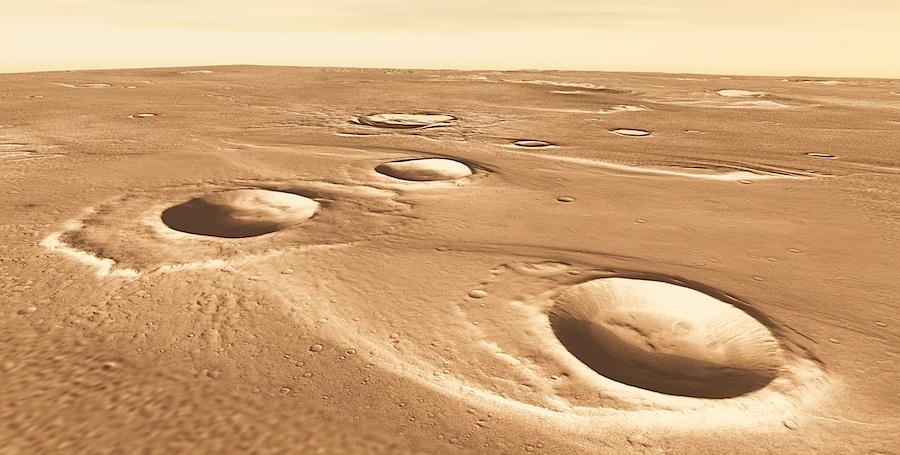

CRATERS AND DEPRESSIONS open "windows" into the subsurface terrain of northwest Arabia Terra. In the bottoms of some depressions lie deposits that formed under different environmental conditions than Mars has at present. This view (which has no vertical exaggeration) looks toward the north-northeast. (A 330 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

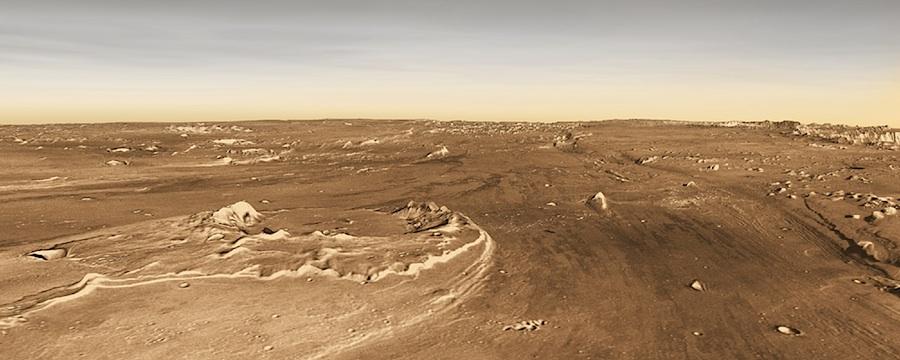

SO WHERE'S THE ALIEN CIVILIZATION? The famous mesa formerly known as The Face lies in the foreground at right, where it is slowly eroding along with the other mesas in Cydonia. About 300 meters (1,000 feet) high, its north and east sides (seen here) are covered with "pasted-on terrain." This is the term geologists give to a mantle of material that may be ice-rich and which they think was deposited during the last Martian ice age, more than half a million years ago. This view looks south. (A 340 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, check out Cydonia: Martian Mystery Region. |

FRESHNESS AND CLARITY. Tooting Crater, named for a suburb of London, offers scientists a clear look at a fresh medium-size impact. This view, which looks toward the northwest, shows in the foreground the rampart that piled up about 80 meters (260 feet) high when the debris flowing from the impact came to rest. Here the rampart lies about 40 kilometers (25 miles) from the rim. (A 300 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, check out Tooting Crater's Tangle Tale.

|

SLIP-SLIDING AWAY. The impact of a meteorite near the edge of Noctis Labyrinthus appears to have set off an enormous landslide into the canyon. The crater (left center) is about 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) wide, and the landslide stretches for about 25 km (16 mi). Compare this slide's extent with the much smaller slides that lie at the foot of many sections of the canyon wall. This view looks west from an altitude of about 20 kilometers (12 miles), and there is no vertical exaggeration. (A 9 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, see What Triggered a Martian Landslide? |

SPILLWAY. Looking upstream in Ares Vallis, the broad channel almost disappears into the scenery, despite being roughly 100 kilometers (60 miles) wide here. At left center, a partly destroyed crater named Oraibi stands at the head of a mid-channel island, streamlined into a teardrop shape by the floodwaters. The lack of a narrow meandering channel, such as is found in many large terrestrial rivers, suggests the floods here were massive but brief. The vertical exaggeration is 1.5x. (A 430 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

OUT OF ARABIA. Mawrth Vallis makes a snaky groove as it descends from the highlands of Arabia Terra in the right background. The dark rough areas in the foreground contain deposits of weathered clays that are evidence of a wet period early in Martian history. The clays could contain microscopic traces of life if a Martian biosphere existed. NASA may land the Mars Science Laboratory rover in the smooth area at right foreground, just outside the rim of the large crater visible in part on the right. This view looks southeast and has a 1.5x vertical exaggeration. (A 430 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, see In the Groove: Mawrth Vallis. |

SPECTACULAR SCENERY lies everywhere in Melas Chasma, part of the great Valles Marineris rift. But scientists' attention is focusing mostly on the low hills scattered across the valley floor, left center. These have layered deposits that include sediments formed underwater, and they might preserve traces of an early Martian biosphere, if any such existed. This view (which has a vertical exaggeration of about 2x) looks across Melas toward the northwest. (A 690 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

ON THE EDGE of Terra Sirenum, lava flows and rugged terrain intermingle, as volcanic eruptions from Arsia Mons in Tharsis reach southwest to the cratered highlands. This view looks north over an impact crater 43 km (27 mi) wide, and has no vertical exaggeration. (A 440 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

HIGHLAND'S END. The Martian highlands stretch away toward the horizon in this view that looks south over Nilosyrtis. Directly in the center lies the mouth of a large channel that leads up to an ancient, sediment filled crater. The light patch at left center was a proposed landing site for the Mars Science Laboratory rover — but this site lost out to others elsewhere on Mars. No vertical exaggeration. (A 330 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

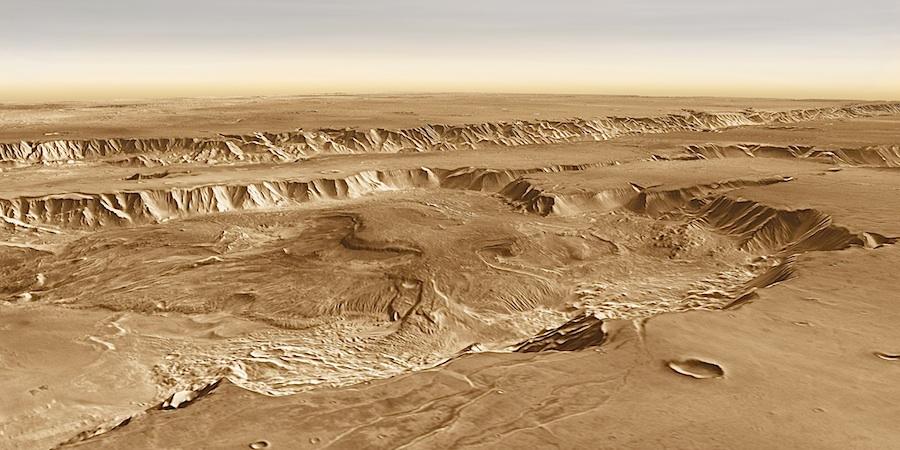

HEAPS OF LAYERED DEBRIS lie in many parts of Valles Marineris, including western Candor Chasma. Remote observations from orbit have found these layered deposits contain abundant amounts of minerals that formed in water. For a time, these earned Candor a place on the potential target list for NASA's next rover, the Mars Science Laboratory. Difficulties with winds and ground surface roughness, however, forced planners to look elsewhere. This view is across western Candor toward the south-southwest. (An 840 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (no vertical exaggeration).To explore this area further, check out Bath Salts in Candor Chasma? |

A ROLLING SURFACE marks Nili Patera, the summit region of Syrtis Major, a large, but low-rise volcano. Inside Nili, scientists have found both ordinary basalt lavas and flows of dacite, a different kind of lava that indicates that molten rock has evolved chemically within the volcano. This view looks southeast. (A 370 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore this area further, check out Complex Lavas In Nili Patera.

|

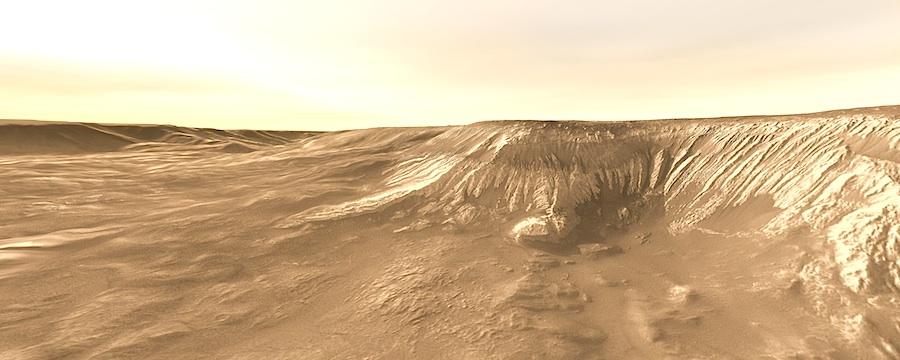

FINE-SCALE GULLIES ETCH the walls of the mesa that fills much of Hebes Chasma. Loose debris has settled in places, smoothening the slope. The origin of the sediments that built the mesa remain unclear, but its layers include debris from volcanic eruptions, plus dust and fine material that fell from the air. In addition, water collected within Hebes during part its history, so lakebed deposits are also likely. This view looks west. (A 530 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (no vertical exaggeration).To explore this area further, see History's Layers in Hebes Chasma. |

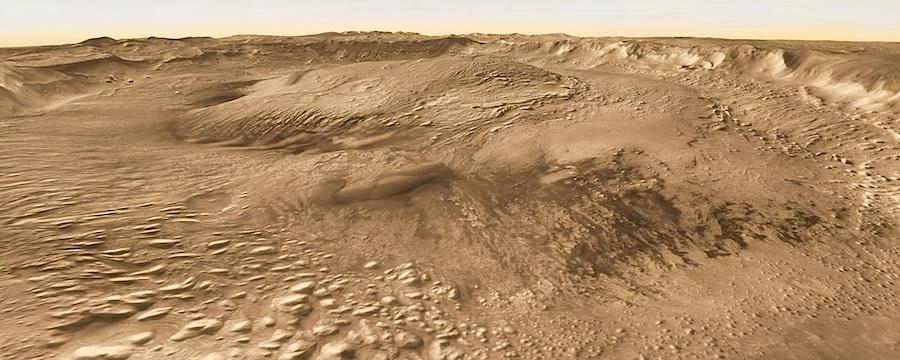

FOR BILLIONS OF YEARS, winds have swept across the oldest landscapes of Mars, alternately depositing sand, dust, and other debris — and then eroding them away, in an endless cycle of burial and exhumation. This view looks northwest across a nameless crater in Arabia Terra — note the wind-sculpted hills (bottom and left, and on the central mound) as well as the dark sand dunes at right. (An 800 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 3x). To explore this area further, see Winds and Streaks of Arabia.

|

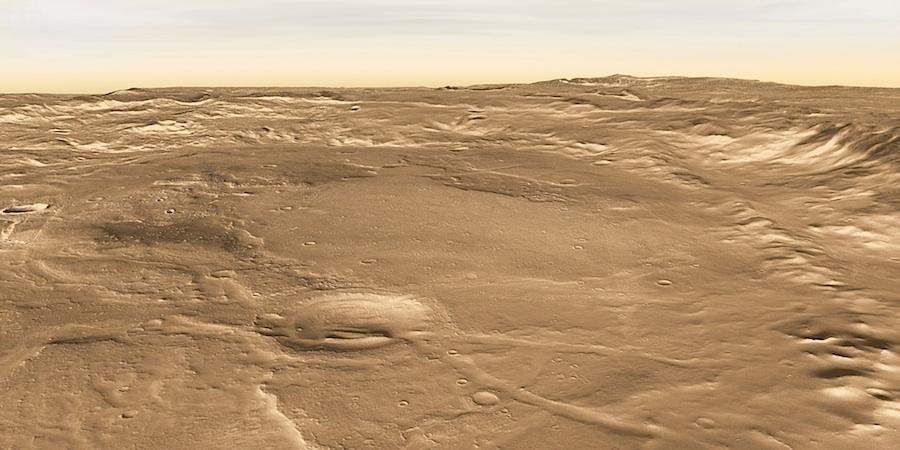

THE SHALLOW BOWL OF A LARGE CRATER has collected debris for most of Mars' 4.6-billion year history. Currently, however, geological forces are slowly removing the sediments. This view looks east. (A 600 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore this area further, see the THEMIS feature article, Erosion and Exhumation. |

DRY LAKEBED. A small basin (center foreground) lies below the southern rim of Melas Chasma, part of Valles Marineris. The basin likely holds ancient lakebed sediments, which earned it a place on the list of potential landing sites for NASA's advanced Mars Science Laboratory rover. Unfortunately, mission operation difficulties forced scientists and mission planners to drop it from consideration. This view looks west down Melas Chasma. (A 480 kB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (no vertical exaggeration). To explore this area further, check out An Ancient Lake in Melas Chasma? |

A DEEP, SPRAWLING BASIN, Juventae Chasma has ridges and hills built of sulfate minerals, including gypsum, that formed under wet conditions. One such hill lies at center in the image (which looks northeast). (A 1.8 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 3x).To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

NEITHER A ROAD NOR A FLOOD CHANNEL, this wide trough in Nili Fossae is a block of crust that dropped between two faults. At one time, this site was on NASA's short list of landing places for its next Mars rover, but the site was passed over in favor of others. The trough spans about 26 kilometers (16 miles) wide, and the hills flanking it contain clay sediments, which point to water (and potential life) in the past. This view looks southwest. (A 1.1 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

RUGGED, FINGER-LIKE MESAS REACH south into Terby Crater (170 km wide), which contains sediment layers going back at least 3 billion years in Martian history. It's a record book waiting to be opened. The sediments in the mesas may preserve a record of early Mars when the Red Planet might have held life. This view looks northwest. (A 1.5 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

WHEN SLABS OF ROCK BROKE OPEN in Iani Chaos, groundwater gushed out of the fractures and poured northward through Ares Vallis, on the horizon at center. The remaining mesas and buttes form what scientists call chaotic terrain, a highly apt term. This view looks north. (A 3.5 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 3x).To explore this area further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

ICE AND DUST make intricate layers at the edge of the polar cap. As scientists study the sequence of layers, they are unravelling the recent climate history of Mars. This view looks to the northeast. (A 3.6 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore this area in more detail, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

IMMENSE FLOODS RACED northward through Maja Valles, carving the valley channel and leaving streamlined island-mesas behind craters. At left center lies one crater that formed after the Maja floods were over, as seen by the intact apron of debris surrounds it. This view looks toward the northeast. (A 2.7 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore Maja further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

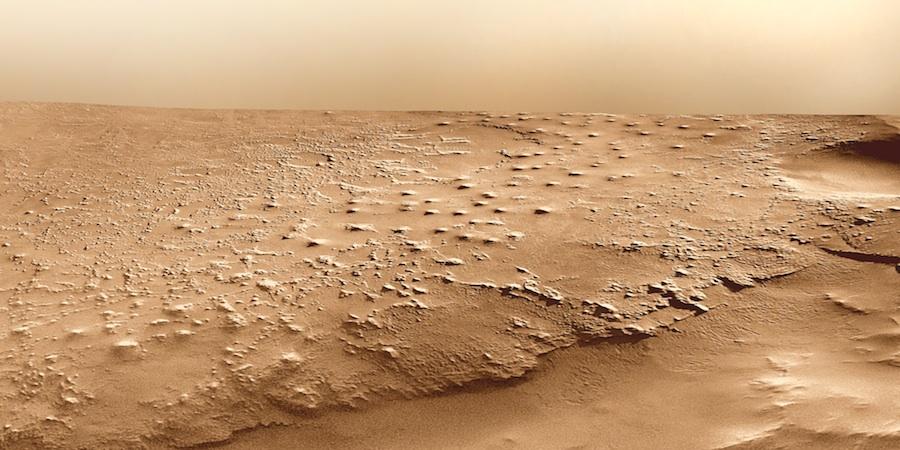

GONE IN THE WIND. Erosion is slowly removing a thick pile of sediments that may have once filled a crater in eastern Meridiani. Note the layering in the foreground of this view looking northwest.. (A 5 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore Eastern Meridiani further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

WATER POURED OUT of the mouth of Uzboi Vallis (center) into Holden Crater through its southern rim. The water laid down layers of sediments inside Holden. One possible landing site for the Mars Science Laboratory rover is the flat, smooth area at right center, close to where the channel cuts through the rim. This view looks toward the southwest. (A 1.3 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore Holden Crater further, see Where Waters Ran. |

AN ANCIENT RIVER DELTA lies at right foreground inside Eberswalde Crater. This view looks south, with Holden Crater (154 km wide) in the distance. Exploring the delta's sediments would be a planetary geologist's dream, but landing the Mars Science Laboratory rover safely there may prove highly difficult given the rough terrain. (A 1.4 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To explore Eberswalde further, check out Where Waters Ran, which also covers Holden Crater. |

A CURVING RIM is about the only clue this snow-capped bluff in the Martian Arctic is an old impact crater, full to overflowing with polar debris. Named for a town in Siberia, Udzha (OO-dja) Crater spans about 45 kilometers (28 miles) wide. This view, looking toward the northwest, reveals Udzha surrounded by dark, stratified layers mostly covered with bright deposits of water ice. In a few places, the crater's sharp-edged, rocky rim peeks from under the polar cap's layers. (A 3.4 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration about 2x). To learn more, see the The Snows of Udzha. |

ESCAPING GROUNDWATER undermined the surface, causing pits and troughs to form, such as this one in Coprates Catena, part of the Valles Marineris canyon system. The white patch in the middle distance is a deposit of sulfate minerals left when a temporary lake in the trough evaporated. This view looks southeast. (A 2.3 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk. To explore Coprates Chasma further, check out the THEMIS feature article. |

IN THE GROOVE. Impacts, floods, and tectonic forces have all left traces on Ares Vallis, a Martian outflow channel. This view looks to the northwest, down the scoured channel toward Chryse Planitia. Outflow channels formed when massive floods of water poured out of the ground early in Martian history when the planet likely had a thicker atmosphere and a warmer climate. Scientists estimate the floods had peak volumes many times today's Mississippi River. Tear-drop mesas extend like pennants behind impact craters, where the raised rocky rims diverted the floods and protected the ground from erosion. While Ares Vallis is not the widest or deepest outflow channel, it extends for nearly 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles). (A 4.4 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (no vertical exaggeration). To explore Ares Vallis further, check out the THEMIS feature article about this place. |

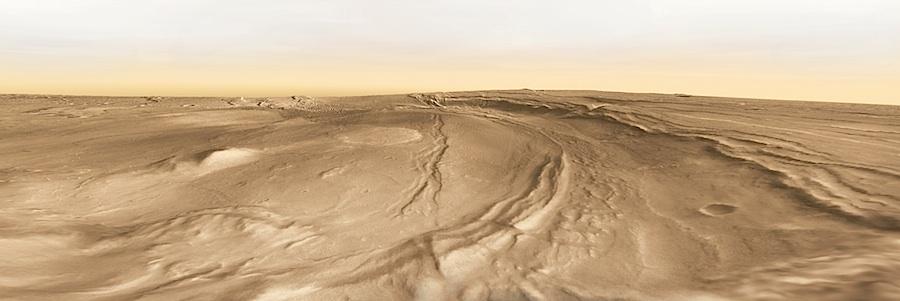

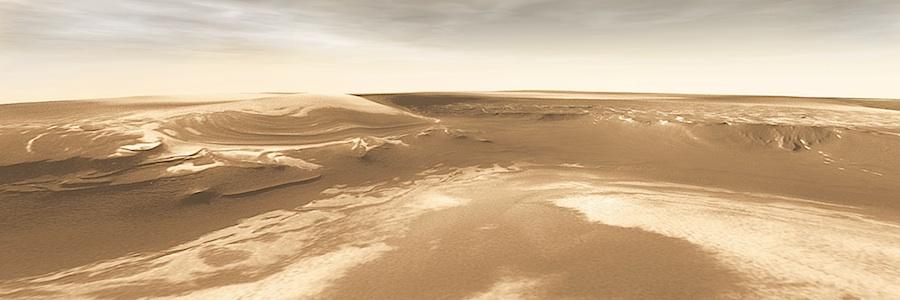

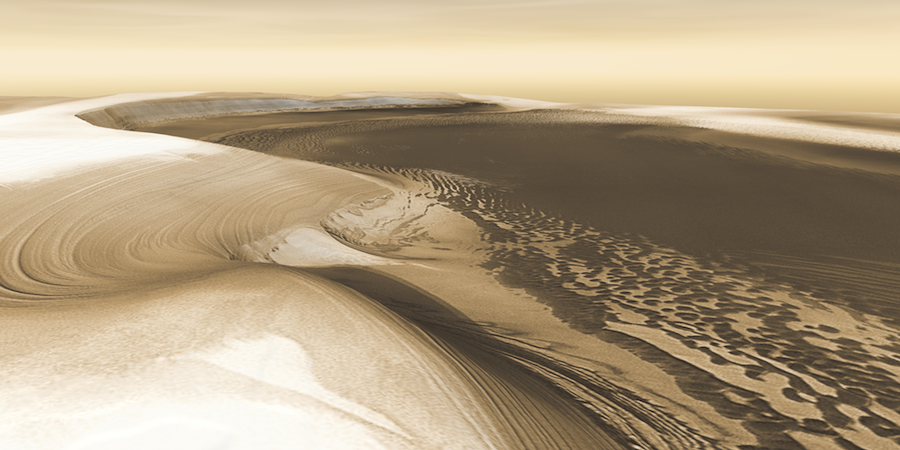

LAYER CAKE. Climatic cycles of ice and dust built the Martian polar caps, season by season, year by year — and then whittled down their size when the climate changed. Here we are looking at the head of Chasma Boreale, a canyon that reaches 570 kilometers (350 miles) into the north polar cap. Canyon walls rise about 1,400 meters (4,600 feet) above the floor. Where the edge of the ice cap has retreated, sheets of sand are emerging that accumulated during earlier ice-free climatic cycles. Winds blowing off the ice have pushed loose sand into dunes, then driven them down-canyon in a westward direction, toward our viewpoint. (A 9 MB version of the image is available.) Credit: NASA/JPL/Arizona State University, R. Luk (vertical exaggeration 2.5x). To explore this feature in greater depth, check out Dunes and Ice in Chasma Boreale. |